Street Photography

by Philip Greenspun; created June 1999 and revised January 2007

Site Home : Photography : Street Photography

by Philip Greenspun; created June 1999 and revised January 2007

Site Home : Photography : Street Photography

"Stare. It is the way to educate your eye, and more. Stare, pry, listen eavesdrop. Die knowing something. You are not here long."

Walker Evans (in a draft text to accompany the hidden camera subway photographs)

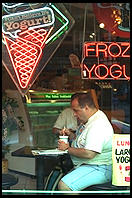

The best thing about street photography is that it is possible for the final viewer of a print to see more than the original photographer. One of the great things about a city is that more things are happening, even within a small neighborhood, at any moment than any human can comprehend. Photography allows us to freeze one of those moments and study all of the small dramas that were taking place.

|

black dog in the corner |

|

photographer in the upper right corner |

|

Venice Beach, California, even weirder and more varied when frozen in time |

Garry Winogrand is famous for having exposed three rolls of Kodak TRI-X black and white film on the streets of New York City every day for his entire adult life. That's 100 pictures a day, 36,500 a year, a million every 30 years. Winogrand died in 1984 leaving more than 2500 rolls of film exposed but undeveloped, 6500 rolls developed but not proofed, and 3000 rolls proofed but not examined (a total of a third of a million unedited exposures).

This is the kind of dedication that you need to bring to a street photography project if you hope to achieve greatness.

The classic technique for street photography consists of fitting a wide (20mm on a full-frame camera) or moderately wide-angle (35mm) lens to a camera, setting the ISO to a moderate high speed (400 or 800), and pre-focusing the lens. Pre-focusing? How do you know how far away your subject will be. It turns out that it doesn't matter. Wide angle lenses have good depth of field. If your subject is 10 feet away and the lens is set for 12 feet, you'd probably need to enlarge to 16x20" before noticing the error, assuming a typical aperture. This is why the high ISO setting is important. Given a fixed shutter speed, the higher the ISO setting, the smaller the aperture. The smaller the aperture, the less critical it is to focus precisely. The extreme case of this is a pinhole camera, for which there is no need to focus at all.

Street photographers traditionally will set the lens at its hyperfocal distance. This distance depends on the lens focal length and the aperture but the basic idea is that it is the closest distance setting for which subjects at infinity are still acceptably sharp. With fast film and a sunny day, you will probably be able to expose at f/16. With a 35mm lens focussed to, say, 9 feet, subjects between 4.5 feet and infinity will be acceptably sharp (where "acceptable" means "if the person viewing the final photograph doesn't stick his eyes right up against it").

A modern alternative is to use a camera with a very high-performance autofocus system and a zoom lens. The Canon EOS bodies coupled with the instant-focusing ring ultrasonic motor Canon lenses (about half of the EOS lenses use these motors) are an example of what can work. How important is modern technology? Testing out the Mamiya 7 rangefinder camera, a mechanical design straight out of the 1920s, doing some street work in Guatemala, my yield of good images was as high as it ever was with the Canons.

Whether you go modern or traditional, many of your pictures will be ruined due to poor focus, subject motion, hasty composition, etc. Don't feel bad if you only get one great picture out of 1000. If you're using a digital camera, you won't even have to lose sleep over how much film and processing you're wasting.

|

The photo at left has a subject in sharp focus. The photo at right has more life. Both probably would need to be edited out. |

|

A few more from Mexico...

|

Miami, 1995, from Costa Rica; Canon EOS-5, 35-350 lens, program autoexposure, Fuji Super G + ISO 400 neg film

This photo, taken from the passenger seat of a car stopped at a red light, photo illustrates

the capabilities of the |

a few from Sweden...

and Germany...

and Ireland..

and Israel (Ireland's neighbor in the UN, separating Israel from Iraq)..

China is one of the world's best places for street photography because (a) there are so many people, (b) so much happens out in the open. Here are a few images from China:

Japan is a good place to see extremes, either people practicing ancient ways or people overwhelmed by modernity. Here are some images from Japan:

Text and images copyright Philip Greenspun.